The world’s central banks are engaged in a major policy reversal to prevent the world economy from sinking into unexpected recession.

Alarmed by an economic slowdown and stress last year in financial markets, they are calling off interest-rate increases sooner than expected and in some cases easing monetary policy.

In many cases, the central bankers are boxed in, with few policy tools available to cushion their economies.

Collectively, though, economists say the central bankers have reduced market risks and helped ease financial conditions in a way that should keep expansions—nearly a decade long or older in the U.S. and China, while fragile and short-lived in Europe and Japan—going through 2019.

It started with the Federal Reserve. Six months ago, Fed officials thought they would raise short-term interest rates three times in 2019 on the way toward a policy rate near 3.5% in 2020. Fed officials recently signaled they have paused for now, with short-term rates just below 2.5%. Their actions and words strongly suggest they could be done altogether.

The Fed’s reversal after last year’s market turbulence changes the contours of the expansion and helps preserve an outlook for continued growth, said Goldman Sachs Chief Economist Jan Hatzius.

“The Fed was trying to tighten financial conditions gradually (last year) and then it got a much bigger and more rapid tightening than it expected,” he said. He now sees a sharp drag on U.S. economic growth early this year and gradual improvement as the year progresses, rather than the steady slowing he previously expected.

“It could be a year from now we’ll find this was a pause that ultimately doesn’t really change the outcome that much,” he said.

With the Fed taking an easier stance, other central banks have less pressure to raise rates. J.P. Morgan economists see rates 2 percentage points lower in Brazil than they expected a few months ago, and they see India cutting rates. Australia is expected to reduce rates, too, and rate increases are expected to be put off in Canada and the U.K.

“We’re clearly seeing a dovish tilt that is broadening out,” said J.P. Morgan’s chief economist, Bruce Kasman.

Europe and Japan are evidence that the central bankers have little room for error. Last week, the European Central Bank reduced its 2019 projection for inflation to 1.2% from 1.6%, well below its 2% target. It also cut its growth forecast to 1.1% from 1.7%.

In normal times, a central bank would cut interest rates when confronted with such a big inflation miss and deteriorating growth outlook. But the ECB’s target short-term interest rate is already negative and the scope to restart a bond-buying program that ended three months ago constrained. The ECB said it would put off rate increases and expanded a special bank-lending program, but Mr. Kasman found the move inadequate for the moment.

“The ECB is moving here, but its limited toolbox makes it quite vulnerable,” he said.

Because the central bankers have limited room for error, they are more sensitive than they were in decades past to signs that growth or inflation might be slowing more than expected. They call it a “risk management” mindset. They have unlimited space to fight accelerating inflation with higher interest rates and little-to-no space to fight slowing inflation with lower rates. Thus they are doing whatever it takes to avoid such shortfalls.

“Seeing how central banks have adjusted fairly rapidly to the data coming in does reduce some of the downside risks,” said Kristin Forbes, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and former member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee.

In a paper presented at the Brookings Institution last week, former U.S. Treasury Secretary and White House adviser Lawrence Summers suggested this risk imbalance could now be an entrenched feature of the economic landscape. A neutral interest rate that neither stimulates the economy nor constrains it is 3 percentage points lower than it was a generation ago, he said, putting it closer to zero on a regular basis. That means central banks could be living in a state of high alert for years.

In some respects, the situation mirrors a global slowdown just three years ago that sparked synchronized policy easing by global central banks. The Fed then also led the way, scrapping plans to raise rates several times, instead lifting rates just once at the end of 2016.

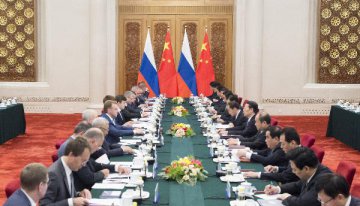

Today’s episode is complicated because it involves a broad range of political uncertainties, such as the Trump administration’s confrontations with China over trade and the U.K.’s plan to leave the European Union.

“These are a different kettle of fish from 2016,” said Lewis Alexander, chief U.S. economist for Nomura Securities. “The very stable international policy regime that we’ve been living with for decades may not be as stable as we thought it was.”

Add China’s slowdown to the list of uncertainties for the global outlook. Its policy makers are trying to stimulate growth, too, with an emphasis on fiscal policy. But they are also constrained, fearing that massive stimulus—what they call “flood irrigation” from years past—could lead to excessive borrowing that damages China’s economy in the long run.

In short, the risk may be diminished after the latest reversal by central banks, but it’s hardly gone.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Latest comments