Investors dumped Boeing stock after Sunday’s deadly plane crash. But the lesson of history is that such accidents, however tragic, do surprisingly little damage to the business of selling aircraft.

Unruffled

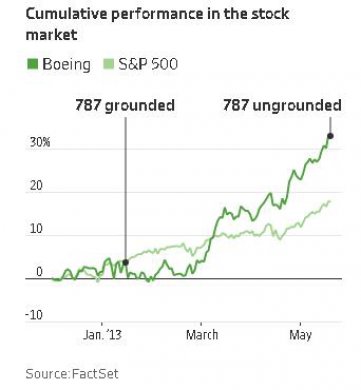

When 787 jets were grounded by U.S. regulators in 2013, Boeing's stock-market under performance didn't last long

Cumulative performance in the stock market

Source: FactSet

Chinese and Indonesian authorities called Monday on their domestic airlines to ground all Boeing 737 MAX jets, following the crash of an Ethiopian Airlines flight that killed all 157 people aboard. This is the second deadly incident in six months involving the 737 MAX—a plane that only started flying in 2016. The Lion Air crash in October killed 189 people.

The 737 MAX’s automated stall-prevention feature has been under scrutiny for its role in the earlier crash, especially as the company had withheld some details of the system’s potential hazards. It is unclear whether a design flaw played a part this time around, but U.S. regulators will likely crack down on Boeing if it is shown it did.

In a worst-case scenario for the company, the 737 MAX would need an expensive overhaul. Airlines could also demand compensation for grounded planes and cancel orders.

Boeing stock fell 12% at the open, wiping roughly $30 billion off the manufacturer’s market value.

If precedent is any guide, however, the fallout will end up being less dramatic for the jet maker than investors seem to assume.

An investigation has been launched after an Ethiopian Airlines Boeing 737 MAX 8 crashed shortly after takeoff on Sunday, killing all on board. WSJ aerospace reporter Robert Wall discusses the possible focus of the investigation, and more. Photo: Getty Images

In 2013, Boeing faced a big disruption when the Federal Aviation Administration halted all flights using its 787 Dreamliner, which was then state of the art, following several incidents and emergency landings caused by the plane’s faulty lithium-ion batteries. The jets stayed grounded for four months while Boeing designed a fix and waited for a green light from regulators.

Boeing’s shares lagged the broader stock market for a couple of months, but by the time the problem was fixed they had already more than made up for the underperformance. For the whole of 2013, Boeing stock rose 81%, far ahead of the S&P 500.

A clue that investors don’t think Boeing is really in danger of losing market share is that shares in Airbus—the only company that offers a true rival to the 737 MAX, because of its popular A320 narrow-body jet—edged up only about 1% Monday, not much more than the broader European stock market.

The 737 has been flying since 1966 and is the best-selling commercial plane family in history: More than 10,000 have been delivered. Airlines are unlikely to turn away its latest iteration, even if it needs an overhaul. The Lion Air accident doesn’t seem to have affected Boeing’s order book.

Earlier cases tell a similar story. McDonnell Douglas’s DC-10 had a calamitous safety record, yet it stayed in production for 20 years from 1968—and remains in use as a freighter aircraft. Even the 1950s’s de Havilland Comet, whose design flaws led to numerous accidents, enjoyed a multidecade career after a redesign.

The Ethiopian Airlines tragedy, so soon after the Lion Air one, is a blow to Boeing’s image. But for better or worse, crashes don’t tend to affect the popularity of plane models.

Latest comments