ESPOO, Finland—The U.S. and China are waging a war for technological supremacy. Nokia Corp., the onetime cellphone pioneer, is looking to play both sides.

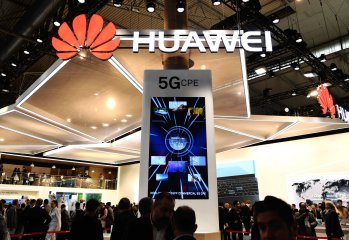

The Finnish company, which had nearly disappeared, has transformed itself into a global manufacturer of telecommunications equipment—such gear as cellular antennas, phone switches, internet routers and new components for next-generation 5G wireless systems—and is now the world’s No. 2 player behind China’s Huawei Technologies Co.

In the U.S., the government has all but barred Huawei sales over fears its equipment could be commandeered by Chinese authorities to disrupt or spy on communications. The Trump administration is pushing such allies as Britain, Germany and Japan to do the same.

That’s a part of Nokia’s sales pitch as the world prepares to upgrade wireless systems to 5G, the superfast technology that could enable driverless cars and internet-controlled factories. Its sales staff has cold-called wireless carriers in countries where the U.S. has stepped up its anti-China rhetoric, pushing its gear as an alternative.

Without secure 5G systems, “essential trade secrets will fall with those networks: airplane innovations, pharmaceutical formulas, electric-car schematics,” Nokia Chief Executive Rajeev Suri said in a February speech.

At the same time, while helping the U.S. wage its campaign against Huawei, Nokia is seeking to build its presence in China. Largely through a joint venture with a state-owned Chinese enterprise, Nokia employs roughly 17,000 in its Greater China region, which includes Hong Kong and Taiwan. That is about triple the number of its employees in Finland. Together, the company runs a factory and six research facilities in the region.

“We want to be a friend of China,” Mr. Suri said in an interview at Nokia headquarters in Espoo, a forested city across the bay from Helsinki. He serves on the Chinese premier’s overseas CEO council, which advises the government on business.

Mr. Suri has said his goal is to be China’s top foreign supplier. Last year, Nokia’s business in its China region accounted for roughly 10% of its sales, €2.1 billion ($2.4 billion).

Nokia Chairman Risto Siilasmaa is the co-head of a bilateral business consortium that China President Xi Jinping and Finland President Sauli Niinisto established. During a June 2017 trip to China, Mr. Siilasmaa announced creation of a Nokia unit dedicated to helping Chinese internet companies expand overseas.

“I believe trust is the foundation of the relationship between China and Finland,” Mr. Siilasmaa said in a speech he delivered in Mandarin during the trip.

The Wireless Final Four

To play both sides of the U.S.-China divide, Nokia is following a strategy used by Finland during the Cold War. The nation allied with European countries while mollifying its eastern neighbor, the Soviet Union.

The playbook seems to be working. In July, Nokia signed a deal worth as much as $1.1 billion to provide equipment and services to China Mobile Ltd. , the world’s biggest mobile carrier by subscribers. Three weeks later, it landed a $3.5 billion deal to sell 5G equipment and services to T-Mobile US .

Nokia has a long way to catch up with Huawei, which began to expand beyond China two decades ago. Huawei found a global toehold by first winning over carriers in developing countries with cheap and reliable gear.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

Can telecommunications be kept secure? Join the conversation below

Huawei has since gained customers across the West. Carriers say the company routinely offers hardware innovations months before Nokia does and is competitive on pricing. Some Nokia leaders don’t dispute the point, said people familiar with company leadership. Huawei has also rebutted the U.S.’s charges, saying it operates independently of Beijing.

Last summer, a Finnish wireless carrier set up a 5G network to test a wireless system from Huawei to deliver high-speed Wi-Fi directly to homes. If successful, it could eliminate visits from a cable guy to hook up the home internet.

Nokia didn’t introduce a comparable product until February.

“Huawei was the only one at this point in time who could deliver to us,” said Veli-Matti Mattila, chief executive of the Finnish carrier, Elisa, which uses network equipment from Huawei, Nokia and Ericsson.

“You can nitpick us on one or two products,” said Mr. Suri, Nokia’s chief executive, “but on the whole, we’re competitive.”

Trees to tires

Nokia’s move from cellphones to telecom equipment fits a history of reinvention. It began in 1865 as a wood-pulp business and was named for Finland’s Nokianvirta River, where it ran a mill. Over a century, Nokia diversified into rubber and electronics, making boots, tires, gas masks and computers.

In the 1980s, Nokia pioneered cellular equipment and phones. Its popular models—including the once-ubiquitous Nokia 3310—kept the company’s share of the global cellphone market above 30% through the 2000s, according to research firm Gartner Inc. In 2008, Nokia held nearly 40% of the market.

Smartphones changed everything, opening an era dominated by Apple Inc.’s iPhone and devices using Google’s Android software. Nokia arrived late to the party with smartphones that customers found difficult to use.

Nokia sold its phone business in 2013 to Microsoft Corp. for $7 billion. By then, its market share was around 14%. The company was left with its telecom-equipment enterprise, which it expanded with the purchase of French rival Alcatel-Lucent for $17 billion in 2015.

The acquisition turned Nokia into a major seller of routers and other infrastructure to cable and internet providers, propelling the company past Swedish rival Ericsson AB to become the industry’s No. 2 player. Only Huawei was bigger.

Nokia hasn’t had a profitable year since 2015. The company has since gone through layoffs and executive turnover. Last year, Nokia reported revenue of €22.6 billion ($25.5 billion) and a loss of €335 million. In January, it announced more layoffs, including 280 in Finland and 408 in France.

Company executives saw a potentially lucrative edge in the American market: Congress had effectively barred Huawei on national-security grounds in 2012, just as the Chinese company had started to make inroads in the U.S.

“We saw the opportunity to be one of the only two companies to offer an end-to-end portfolio, and the only one to do it globally,” said Mr. Siilasmaa, the Nokia chairman, in a recent interview.

From Forests to Phones

Nokia’s acquisition of former American giants Motorola and Lucent helped it earn Washington’s seal of approval. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., a national-security panel, reviewed the purchase of Alcatel-Lucent in 2015 because the deal included Bell Labs, the famed New Jersey research center with a long history of sensitive government work. The panel gave its approval.

As Washington reviewed the potential threat of Huawei technology and the company’s dominant role in telecom equipment, U.S. officials solicited Nokia’s assistance. Company executives met with officials from congressional intelligence committees and the National Security Agency, said people familiar with the matter.

U.S. officials asked Nokia executives to point out any red flags to look for in telecom equipment, these people said, including hardware that could be vulnerable to espionage or cyberattacks.

The company also sought to assuage U.S. worries that Huawei and ZTE Corp. , Huawei’s smaller Chinese rival also targeted by Washington, would emerge as the world’s only telecom suppliers, the person said.

Seeking allies

Nokia has gotten help at home and abroad. Finland’s export credit agency, Finnvera, reached a novel deal in 2017 with its counterpart in Canada for both organizations to guarantee Verizon Communications Inc.’s purchase of Nokia equipment and services, worth at least $1.5 billion.

Usually the bank of the exporting country finances such deals. But Finnvera Executive Vice President Jussi Haarasilta said his agency has been discussing a partnership with the Export-Import Bank of the U.S. about co-financing Nokia equipment sales to other countries.

An official at the U.S. agency said Washington was exploring with Helsinki ways to offer “one-stop-shop financing package” to foreign buyers of telecom equipment from non-Chinese companies, such as Nokia.

In addition, U.S. officials say the Build Act, which President Trump signed in October, could create a new financing corporation that could help companies such as Nokia and Ericsson. It will have more freedom “to ensure its transactions align with U.S. foreign policy,” one official said

Despite the U.S.-led campaign against Huawei, the Chinese company expanded its lead in the global telecom-equipment market in 2018 with a 28.6% share of revenue, compared with Nokia at 17% and Ericsson at 13.4%, according to research firm Dell’Oro Group.

Not long after the U.K. government warned last year that equipment from China’s ZTE posed a national-security threat, Nokia made a pitch to Jersey Telecom, a tiny wireless provider serving islands in the English Channel.

“They said, ‘Given the announcement about ZTE, would you consider switching suppliers?’ ” said Graeme Millar, Jersey Telecom’s chief executive. He decided to stick with ZTE because swapping would cost too much.

A Nokia spokesman said such offers are a standard industry practice.

Mr. Suri, Nokia’s chief executive, has been cautious in public statements about Huawei, rarely naming Huawei or China as he addresses security risks raised by Washington and its allies.

Yet his company is lobbying on behalf of an anti-Huawei measure by the Federal Communications Commission. The FCC proposal would ban rural telecom providers from using federal funds to buy equipment the U.S. deems a national-security threat, which essentially translates into Huawei and ZTE products.

Huawei has argued against the FCC proposal, in part by saying Nokia, too, is a “equipment giant with ties to the Chinese” government.

Huawei cites Nokia’s joint venture with China Huaxin Post & Telecommunications Economy Development Center, an entity controlled by the Chinese government. The Finnish company owns 50% plus one share.

The FCC had no basis “to distinguish between Huawei’s connections with China and Nokia’s (at least) equally strong connections,” Huawei lawyers said in a regulatory filing last August.

Nokia, in its own FCC filing, said Huawei’s allegations were “at best misleading, and at their worst, blatantly dishonest.”

Latest comments